Part 1: COLONIALISM AND SLAVERY AS NECROPOLITICS

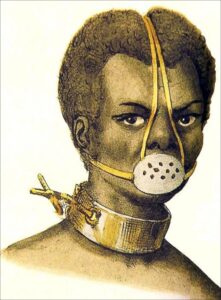

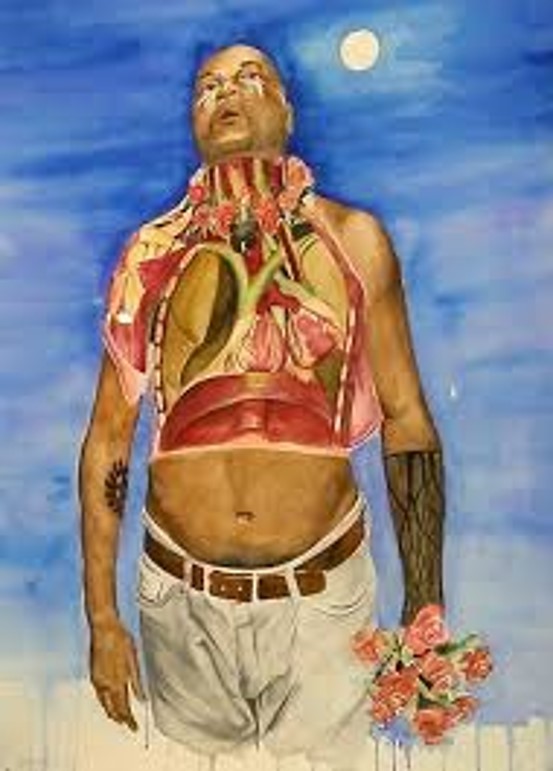

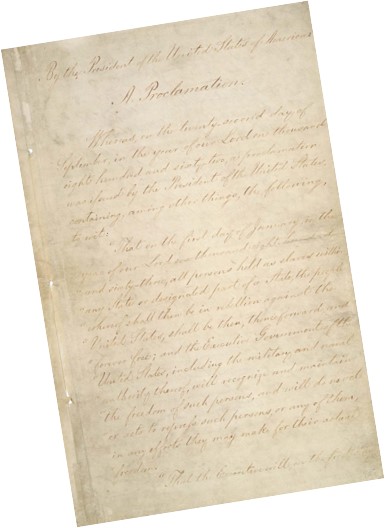

The nations that make up the Americas were born of conquest and dispossession. European explorers devastated indigenous civilizations and 12.5 million enslaved Africans endured the “middle passage” of the slave trade between 1501 to 1875. An unparalleled crime against humanity, racial slavery in the New World was powered by greed and sustained through violence and death. Here we put names and faces to those who, economically exploited and racially oppressed, survived, lived, and resisted, each in their own way. Mounting large-scale insurrections, forming autonomous “fugitive” communities, and demanding full emancipation in writings and speeches, many different historical actors organized resistance to slavery. While slavery was ended via the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) in the U.S. and outlawed by imperial decree (1888) in Brazil, those who were declared legally “free” encountered significant continuity with a slaveholding past, including ongoing racist harassment, violence, and killing.

All wars begin by taking away breath

Who Are the Americans of Whom We speak?

This encounter proved catastrophic for the many indigenous peoples and cultures whose autonomous civilizational trajectories went back thousands of years. Despite their extensive empires and trading systems, fully equivalent to the achievement of Christian Europe, the Islamic World, and China, they became overrun with two types of diseases brought from the “Old World.” Physiological epidemics that attacked susceptible human immune systems and ruthless exploitation that attacked entire social organisms and suffocated their life-building capacities.

Indigenous people in the “New World” were subject to discriminatory legal treatment as “people without reason,” however, their labor produced the silver and other commodity exports that dynamized world trade and sustained the status of European countries as colonial powers. By 1800, less than 2.5 million Europeans had settled in the “New World,” just a fourth of the 10-11 million humans from Africa who arrived as enslaved laborers. They too faced racist stigmatization and a ruthless exploitation that enriched their European overlords, whether at home or in the colonial metropole.

The Trafficking of Enslaved Africans

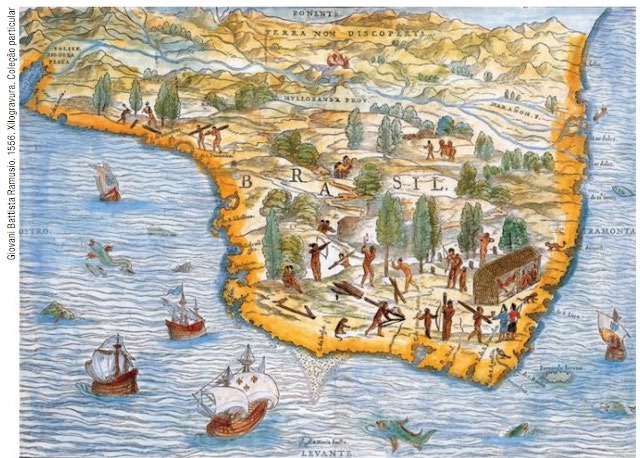

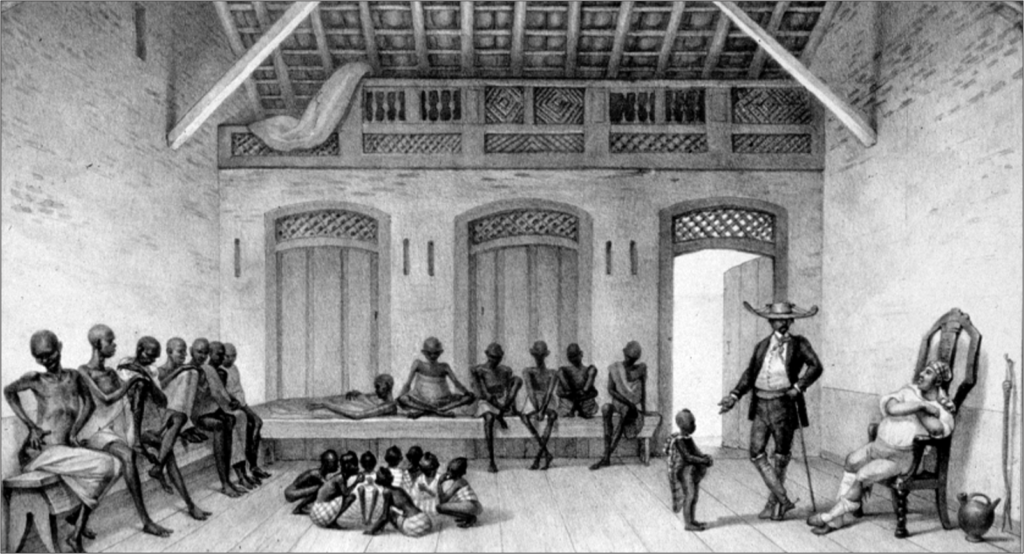

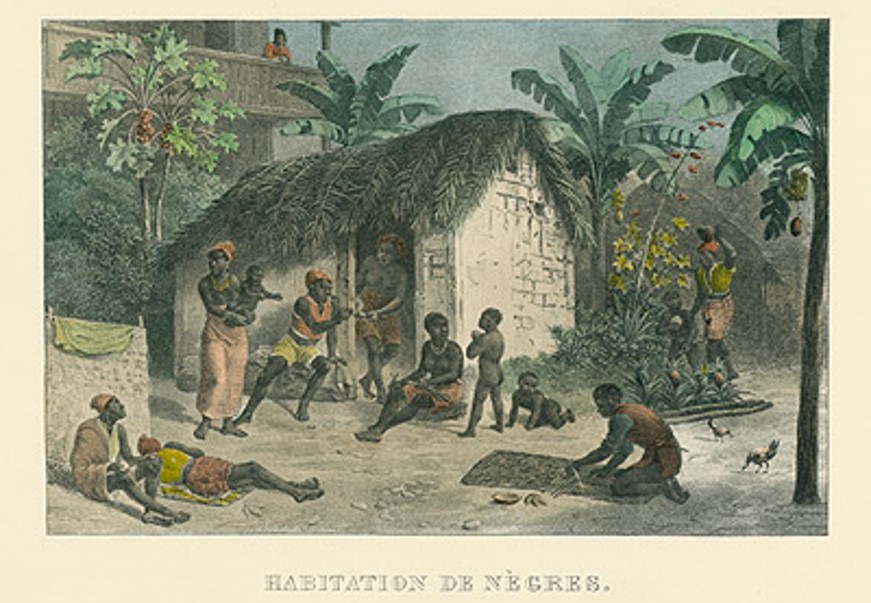

Brazil: From Barter to Enslavement

Brazil lacked the precious metals that drove Spain’s New World Expansion. Its small indigenous coastal populations interacted with visitors at first by bartering Brazilwood trees, the source of a valued red dye, for European tools and goods. Conflict ensued as Portuguese grandees moved to introduce sugar production in the late 16th century. A luxury ‘spice’ much sought after in Europe, sugar was known as the “white gold” and required extensive land, intensive year-round agricultural labor, and an industrial refining process that was impossible without access to a continuing source of cheap labor.

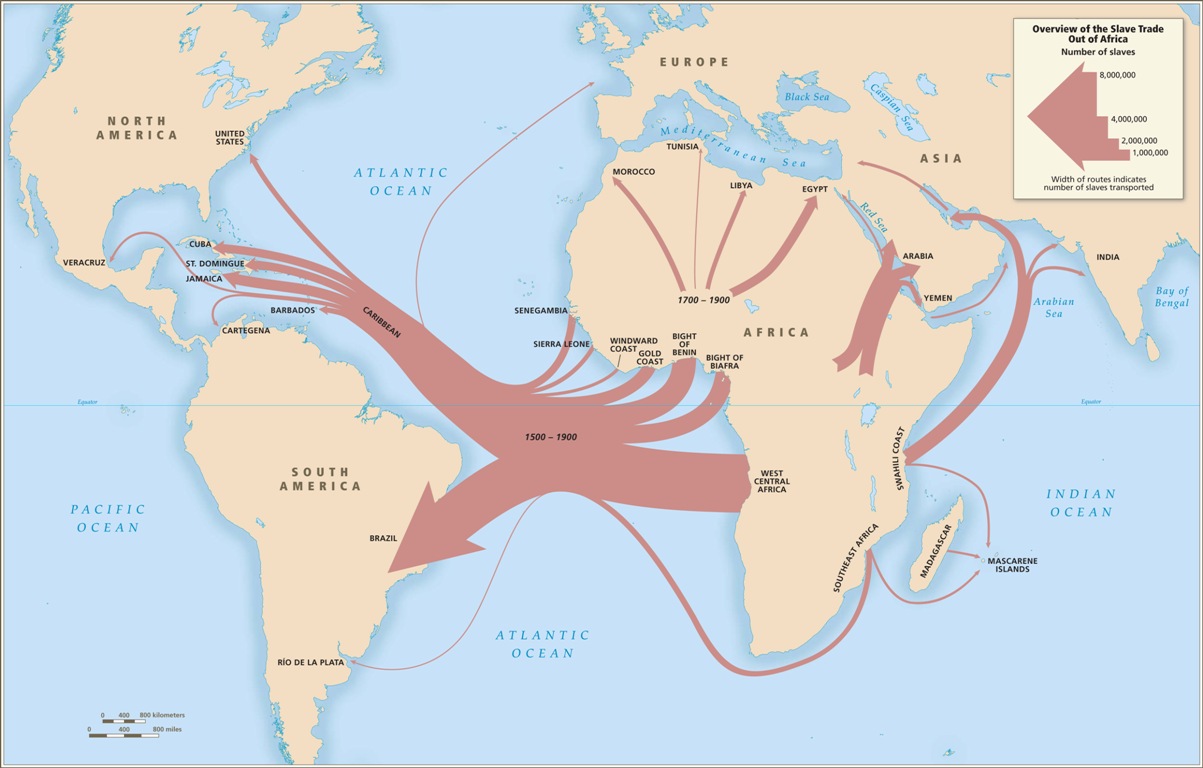

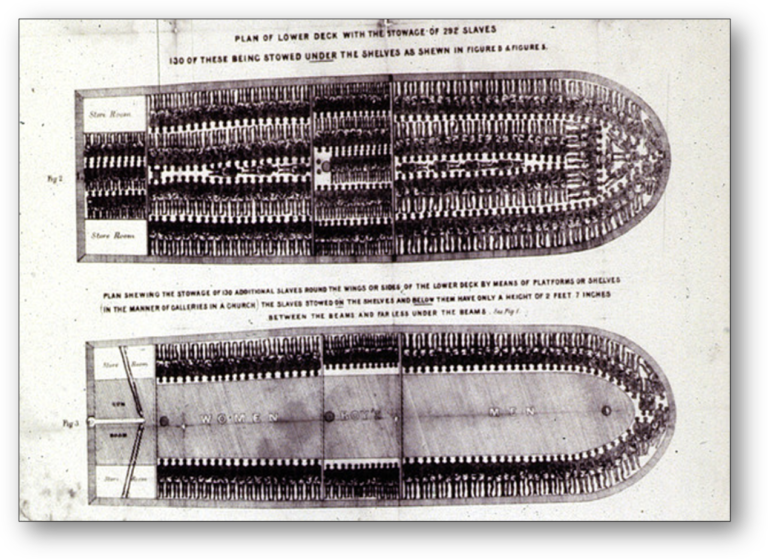

THE SLAVE TRADE TO THE NEW WORLD

A Rolling Genocide Across the Centuries

In its proportions, the trade in Africans to the New World was the largest involuntary migration in modern world history. Over four centuries, 12.5 million people were kidnapped in Africa and embarked on the 36,000 documented voyages by European and U.S. slaving ships between 1501 and 1875. This sea of suffering human beings would have been one percent of the estimated world population in 1800; if adjusted for 2020, it would be the equivalent of 75 million people. When the world moved to end slave trading in the early 19th century, Brazilian slavers would persist even as their own government formally affirmed its illegality but tolerated its operation in practice.

Located so close to Africa, the slave trade to Brazil would actually reach its height in the two decades before 1850 when the trade was finally ended by a threatened English blockade of Brazilian ports.The international trade that legally delivered slaves to the U.S. began in 1619 and ended in 1808. Thus, the arrival of the majority of the enslaved in the U.S. came before the invention of the cotton gin that revolutionized cotton production and invigorated the institution of slavery in the U.S. South.

Slavery in the New World and the trade in Africans that fueled is a crime against humanity to be remembered like the murder of six million Jews by the Nazis, along with others, in the Holocaust in the 20th century. Yet we will never truly understand what happened, how, and with what consequences unless we put names and faces to those who, economically exploited and racially oppressed, survived, lived, and resisted, each in their own way.

Say Their Names and Learn Their Stories

Citing the names and stories of those who died from Covid-19, the Brazilian poet Braulio Bessa has reminded us how statistics and big numbers render invisible the lives lost. As his 2020 poem’s refrain insists: “if cold numbers can’t touch your heart, perhaps their names will.” This applies as well to a one page handwritten and stamped inventory filed in 1738 with the Portuguese colonial authorities in Angola by a returning military expedition. Listing seventy-six captives, it includes the first names of each but reduces most it to their monetary “value.” The exceptions occur most commonly among young women and children:

Bienba/Sungu

child at the breast, 7$000

Mana/Cambia

with the child dying, 6$000

Banba/Sonbi

child at the breast-almost dead, 3$000

Quimano

no child-died on the path, 3$000

Callunbo

huge wound on left leg, 1$000

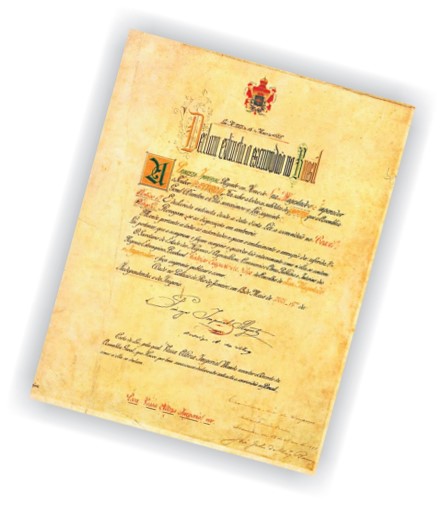

A one-page handwritten and stamped inventory filed in 1738 with the Portuguese colonial authorities in Angola by a returning military expedition. Listing seventy-six captives, it includes the first names of each but reduces most to their monetary “value.” The exceptions occur most commonly among young women and children.

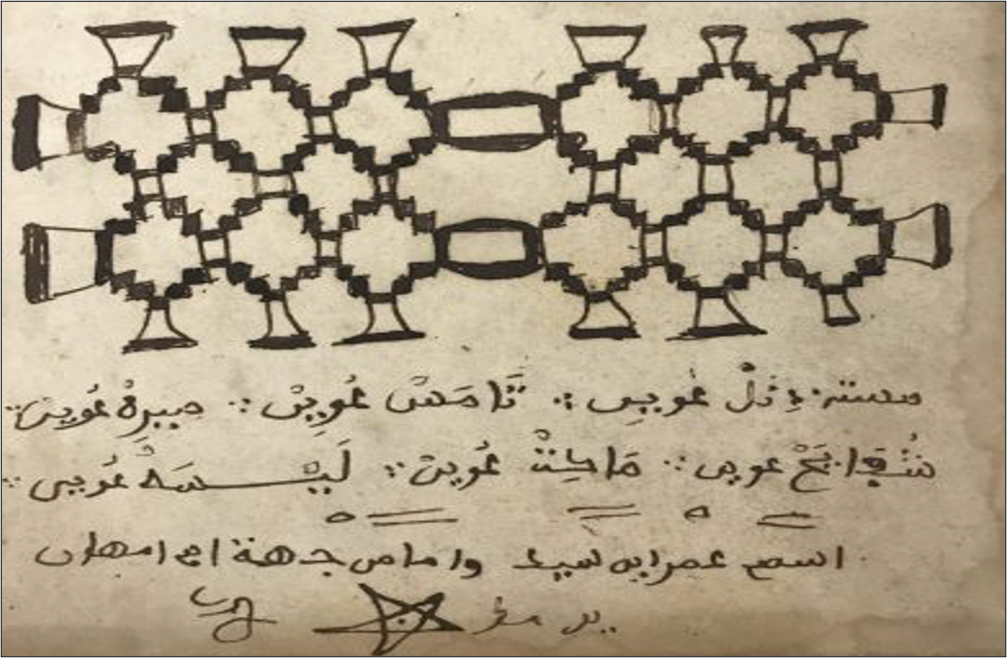

Omar ibn Said (1770-1863), an African-born Muslim enslaved in the Carolinas, offers one such story. Literate in Arabic, the texts that survive—written in that language—include an autobiography as well as an 1813 appeal to the governor for his freedom (denied). It included the following statement in Arabic:

“I wish to be seen in our land called Afrikā, in a place [on] the river called K-bā.”

In Salvador, Bahia, six hundred predominantly Muslim slaves—with their own literate leaders—launched the Western Hemisphere’s largest urban insurrection armed with amulets in Arabic:

Racism: The Poisonous Fruit of New World Slavery

As a form of unfree labor, slavery had long been part of human societies, including Western Europe and Africa, and practiced across religious faiths. Indeed, a third of the population of ancient Greece was enslaved while the European laws governing the institution were derived from the Roman Empire which was famously the site of the world’s best-known early slave revolt led by one Spartacus. Indeed, the word “slave” entered the English language from the French ‘sclavus,’ and referred to the conquered Slavic peoples of the Balkans who were enslaved to produce sugar in Eastern Mediterranean islands such as Crete and Cyprus from the 11th to the 13th century.

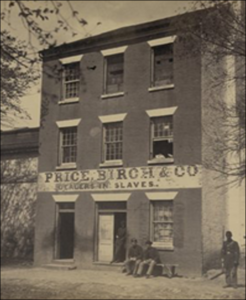

Deliberate Amnesia and the Politics of Denial

Whether in the USA or Brazil, the end of the institution of slavery was followed by a cultivated amnesia that suppressed even the memory of the existence of slave markets and whipping posts. In Rio de Janeiro, private and public excavations in the Gamboa neighborhood in the last quarter century led to the rediscovery of the wharfs of the infamous Valongo slave market which operated until 1831, now designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. Nearby, a family renovating their house discovered the remains of the Cemetery for the New Blacks where slavers unceremoniously dumped the bodies of tens of thousands of as yet unbaptized Africans into pits. In the USA, the recent prize-winning 1619 project of the New York Times recovered images of slave pens and identified locations and auction blocks within the U.S. where the estimated 1.2 million were sold within the USA during slavery’s heyday.

A Crime Against Humanity

In 1823, Brazil’s First Prime Minister José Bonifácio condemned the early Portuguese kings who made it “a branch of legal commerce to seize free people and sell them as slaves” This barbaric traffic, he observed, fomented “robberies, devastations, and wars” in Africa that led to hundreds of thousands deaths in the raids and societal chaos that turned humans into commodities for export. In that very year he wrote, forty thousand slaves were “suffocating in the holds of our ships,” vessels accurately known in Brazil as tumbeiros: coffin-bearers.

What is Banzo?

Life was cheap once on board and ten percent of those embarked would, on average, die from hunger, disease, and abuse before seeing land. Of 12.5 million embarked, only 10.7 million are estimated to have survived the dismal “middle passage” that marked a trade half of whose victims were destined for Brazil. Severely debilitated, many of the newly arrived would die shortly from disease while others were struck by banzo, a word still used by Brazilians today. Banzo has origins in the Quicongo word ‘mbanzu’, meaning thought and memory, and the Quimbundo word for nostalgia, passion, and sorrow, ‘mbonzo.’ In the Novo Dicionário Banto no Brasil, Nei Lopes defines banzo as a “deadly nostalgia that affected black Africans enslaved in Brazil”. The first written record of the word banzo is found in the work entitled “Memory about the slaves and the slave trade between the African Coast and Brazil” presented by lawyer Luis Antonio de Oliveira Mendes at the Lisbon’s Royal Academy of Sciences in 1793:

SLAVE RESISTANCE, REVOLT, AND ABOLITION

Freedom Is a Constant Struggle

The United States

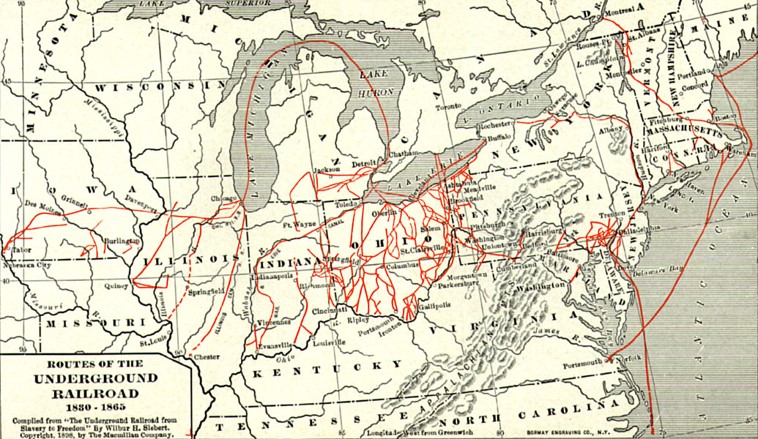

The Underground Railroad

During 1700s-1863 the Underground Railroad was a network of people who helped enslaved people escape to free states and Canada. Aid came in the form of secret routes, safe houses, and stations to eat. It is estimated that more than 100,000 enslaved people found freedom through the underground railroad. The most famous “conductor” was Harriet Tubman. She led people in 13 trips to the South, helping to free over 70 people and gained the name “Moses of Her People.”

Nat Turner’s Rebellion

In Virginia, 1831, Nat Turner, an enslaved man inspired by religion, led the deadliest slave rebellion in American history. Together, he and more than 50 other enslaved people killed more than 50 whites. Fear ripped through the racist white South in the aftermath of the rebellion and led to laws prohibiting the education of enslaved and free Black people. More than a century after the rebellions and his death by hanging, Nat Turner became an important icon to the Black Power Movement.

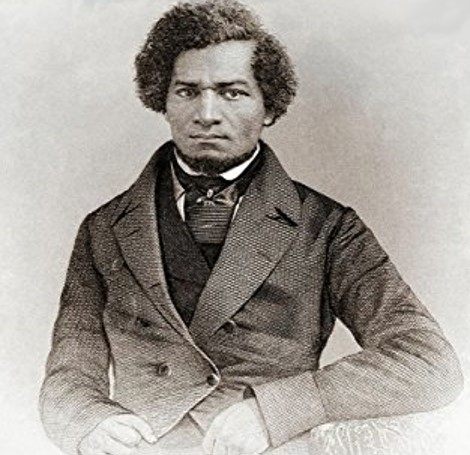

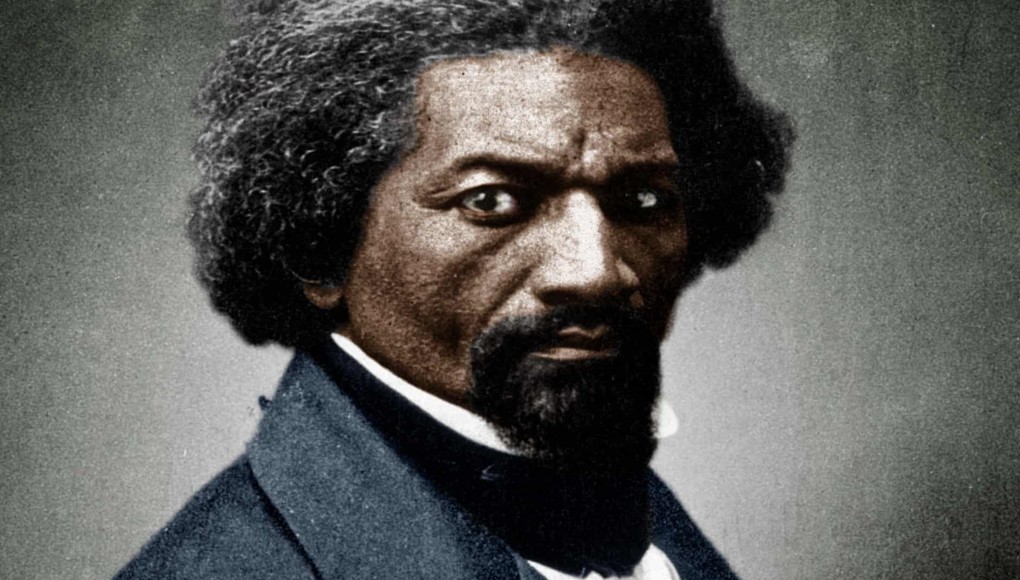

Frederick Douglas

Frederick Douglass is one of the most high-profile abolitionists in United States history. Born into slavery, he learned to read and later escaped from slavery. He was a reformer, abolitionist, orator and became a national leader of the abolitionist movement. He went on to speak on his experiences under slavery throughout the country.

Brazil

Quilombo dos Palmares

The Quilombo dos Palmares, was the biggest community of escaped slaves in Afrodiasporic world. It was the largest ‘fugitive’ community to have existed in Brazil. The quilombo was organized like a small state, with laws and norms, many of which originated from Central African models, given the background of its inhabitants. It resisted for more than a century (1580-1694), gathered around 20 thousand quilombolas (when Salvador, capital of Brazil at the time, had 35 thousand inhabitants), occupying an area size like Portugal. Zumbi was the most important leader and until today they represents the greatest example of black resistance to slavery in Brazil.

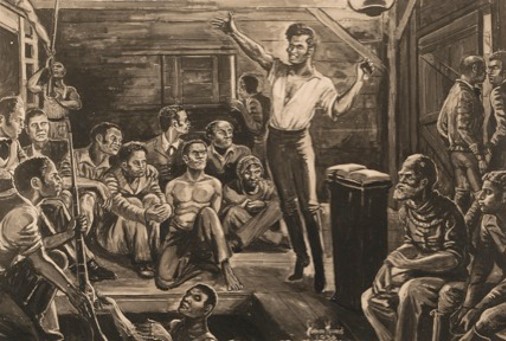

The Malê Rebellion

The Malê Rebellion was an insurrection of African-descended Muslims during Ramadan, in 1835. Involved 600 black men, both free and enslaved, targeted those who did not belong to the African-born, enslaved and free populations. The objective was the seizure of power of the city of Salvador and the mobilization was based on the revolt of the slaves with the horrible living conditions. As a result of the uprising, security forces in the state of Bahia seized and criminalized items they associated with Islam, including documents written in Arabic. Was the most relevant uprising of Bahia. According to Luís Gama, one of the leaders of this revolt would have been his mother, Luiza Mahin, today a symbol of black feminism in Brazil.

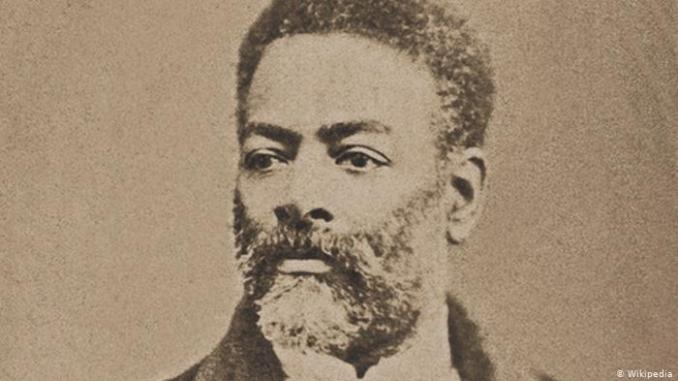

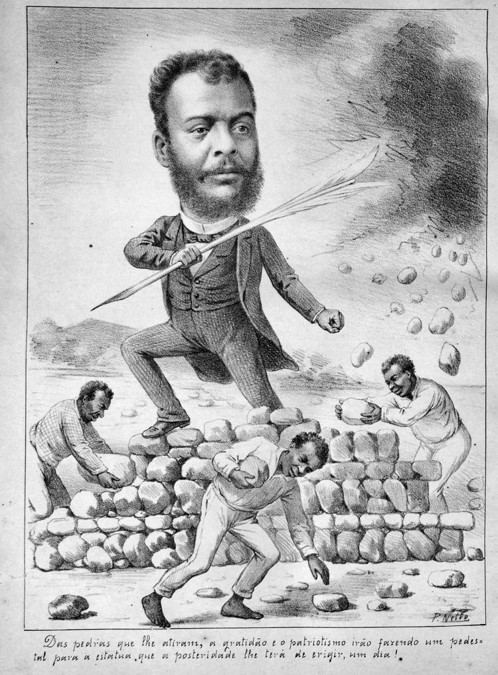

Luís Gama

Luís Gama was a lawyer, speaker, journalist, Brazilian writer. He conquered his own freedom in court and began to work as a lawyer on behalf of the captives, being already at 29 years of age a renowned author and considered “the greatest abolitionist in Brazil”. He guided his life in the struggle for the end of slavery and the monarchy in Brazil, but he died six years before these causes were realized. His funeral was guided by a popular crowd that called him “friend of all”, becoming one of the greatest manifestations of São Paulo in the period.

THE END OF SLAVERY

Promises Unfulfilled

Abolition Versus Emancipation

Abolition But Not Full Emancipation

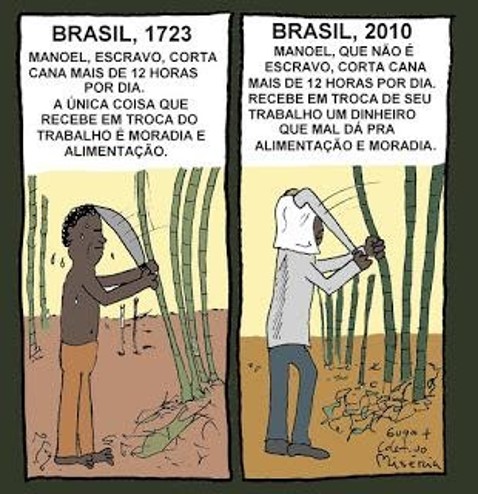

In Brazil, a process of gradual emancipation enacted by slaveholders began in 1866 and culminated on May 13, 1888, through an imperial decree issued by Princess Isabel. Although it freed few slaves, the Golden Law (Lei Aurea) was presented as a gift from above. It ignores years of activism by Black and white Brazilians and massive flights of slaves from plantations in the final years. It is, as Black movements say today, a false emancipation.

André Rebouças on the Unfinished Business of Emancipation

Brazilian abolitionists were critical of the lengthy and gradual cessation of slavery. André Rebouças (1838-1898) was a Brazilian abolitionist, engineer, and inventor. He was one of the main articulators for the abolishment of slavery in Brazil and used what money he had to help found an abolitionist newspaper and helping to create the Brazilian Society Against Slavery.

“We must level this beautiful Brazil,” he said, in order to accelerate the advent of a “Rural Democracy” that would allow this vast country to attack the misery in which most of the Brazilian population was found, including even those who were legally free, but enslaved, according to him, by the “forced salary” of whimsy wages.

“The extinction of slavery led the problem of abolishing misery to the first Plan. The slavery was a great machine to produce proletarians and wretches. It was it that made possible, for three centuries, the most monstrous territorial monopoly ever seen on the surface of the globe. This monopoly has produced urban misery, without ground, air and light, accumulated in pigsties; begging during the day and sleeping at night in human dunghills, it produced the rural misery, without land, without salary, without any compensation, without the slightest idea of fair and equitable distribution between capital and work.”

A Historical Grievance

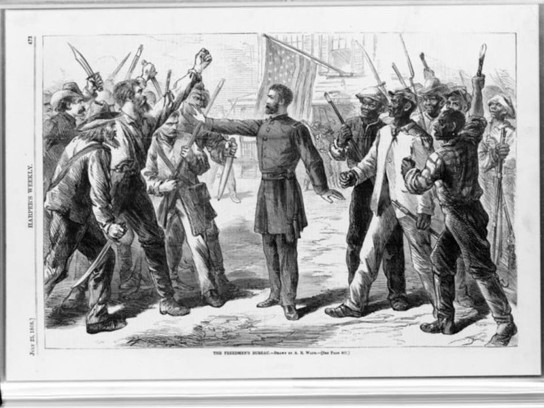

“40 Acres and a Mule”

After the end of the Civil War, the phrase resonated among newly freed African Americans who were promised land as compensation for unpaid labor during slavery. In January 1865, General William T. Sherman issued Field Order Number 15, which set seized coastal land in South Carolina and Georgia for former slaves. Each family would receive 40 acres and Sherman promised to help secure loaned mules. Congress authorized the Freedmen’s Bureau to divide the land into small plots for rental and sale. Nevertheless, President Johnson ordered that most of the confiscated land be returned to its former owners. Black landholders were forcibly removed.

Agrarian Reform and Abolition

José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva (1763-1838), an abolitionist and European educated statesman, was a newly independent kingdom of Brazil’s first prime minister. In 1823, Bonifácio authored an influential piece in which he laid out his vision for the eventual abolition of slavery. He recognized that undertaking agrarian reform was an integral part of abolition. Article 10 of “A Project of Law on Slavery” specified that free men of color would receive a small grant of land for farming as well as other “assistance to establish themselves.” Bonifácio was forced into exile and the new government opted not to adopt its predecessor’s radical program.

Hopes Dashed and Promises Unfulfilled

In the United States, June 19th, 1865, when the last enslaved Americans were made aware of their freedom over two years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, is celebrated as celebrated as Juneteenth.

Radical reconstruction followed abolition in the U.S. Black people were immediately given the right to vote and hold public office. However, hopes were soon dashed at the compromised end of reconstruction in 1877 to win the disputed 1876 presidential election. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white Southern Democrats moved to disenfranchise Black people and strip them of the political and economic gains they had made during Reconstruction. State and local governments enforced segregation through the Jim Crow laws. In Brazil, the new Republic proclaimed in 1889 barred illiterate persons of all colors from voting, a prohibition that remained legal until 1986.

Massacres: Setbacks to Democracy

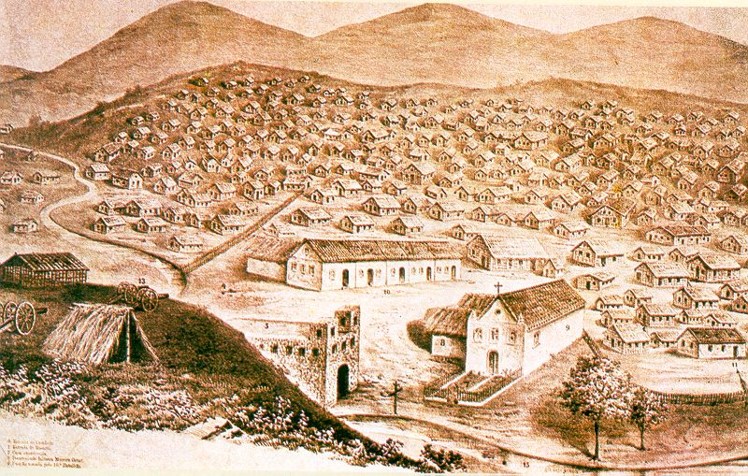

The Canudos Massacre (1896-7)

The War of Canudos is associated with Brazil’s infant Republic, proclaimed in 1889. Antônio Conselheiro was a lay Catholic priest in the arid “backlands” (sertão) of Brazil. He, like many other illiterate, rural people, did not accept the Republic. Conselheiro founded Canudos and thousands gathered around him. The Republic responded violently, sending continued military attacks until the fourth and final attack in 1897 wiped out nearly all the city’s inhabitants. The massacre of over 5,000 rural, poor, and mostly Afro-Brazilian peoples is a powerful instance of state repression.

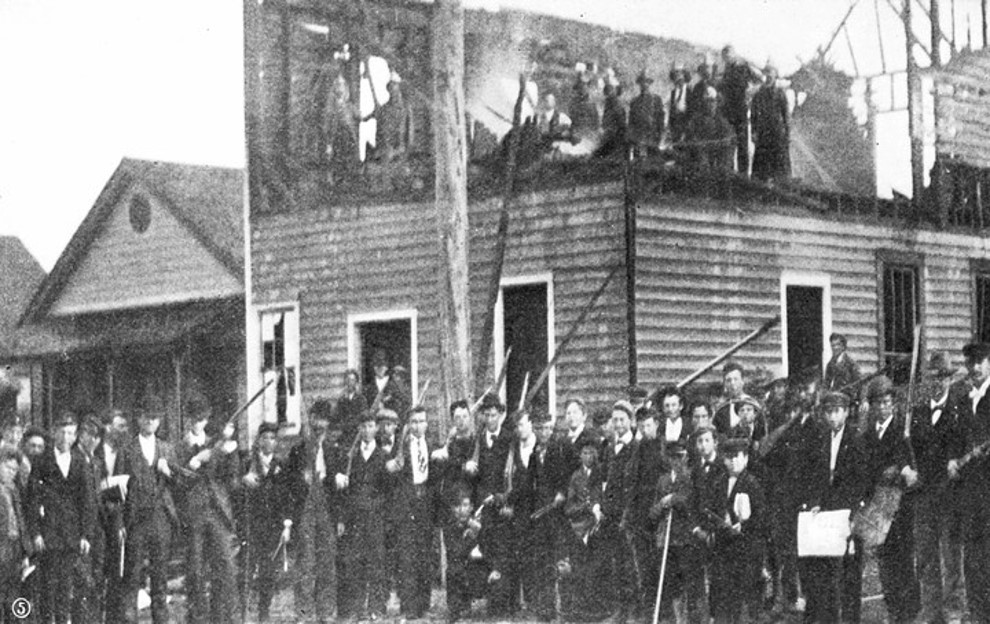

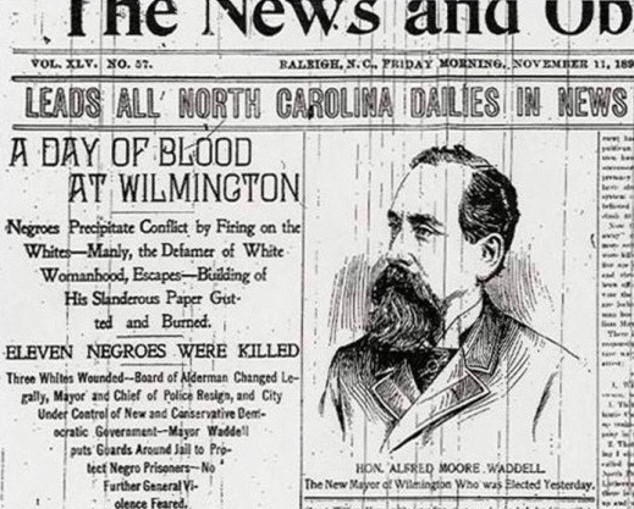

The Wilmington Massacre (1898)

In 1901, George H. White (1852-1918) ended his term as a congressman from North Carolina’s second congressional district. He recognized that his departure wrapped up a 32-year period in which 20 southern Black men served in Congress. In his farewell address, he wrote:

“This … is perhaps the Negroes’ temporary farewell to the American Congress; but … phoenix-like he will rise up some day and come again …”

This website is an ongoing, student-led construction, and we are constantly adding content and references.

Please stay tuned for updates to this and other sections!